Restricting Life at Its Core

California Tightens its Grip on its Water Resources, Threatening the State's Future.

Water is the source of all prosperity and life. Its absence will bring about food insecurity, halt the gears of industrial production, and inhibit our ability to produce reliable energy. Our survival as a society will become precarious. In California, our officials remain apathetic to this reality and press on with misguided policies that will have the catastrophic effect of restricting life at its core.

California’s supremacy in agriculture has been solidified, having established an industry that generates over $50 billion in annual revenues and employs over 420,000 individuals. Its sheer scale is so staggering that it outstrips the economies of entire US states.

Our state's agricultural industry now stands at the precipice of ruin, victim to the narrow-minded dogma espoused by our policymakers.

The San Joaquin Valley presents a troubling glimpse into the States’ future. An astonishing ¾ of nearly one million acres1 of farmland will be forced out of irrigated production. While one may be inclined to attribute this to the ravages of drought or the throes of climate change, the harsh reality is far more disconcerting.

These arable acres will be deliberately rendered desolate in order to comply with the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), a policy imposed by the State that restricts access to groundwater in a last-ditch effort to resolve the groundwater deficit. In the name of sustainability, policies have been implemented that punish farmers for exceeding their state-mandated allotment of groundwater, despite their allotments being woefully insufficient for sustaining their farms.

Of course, without sufficient water, farms go out of business. Farmers lose employment, crop yields decline, and food prices rise. Farmers affected by the SGMA are the sacrificial goat at the altar, offering up their land and way of life for a marginally higher groundwater table.

This is not a mere consequence of bureaucratic ineptitude. It is a calculated and callous attempt to allocate California’s resources in a regressive manner. State officials, entrusted with safeguarding the interests of their constituents, have, in effect, scripted their own demise.

As the farmland is left barren, dust bowls form and create a cloud of noxious particles that can travel far beyond their immediate vicinity. These dust storms suffocate the local environment and the people inhabiting it. If this sounds similar to the plot of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, it’s because it is. In the film, humanity faces extinction due to a worldwide blight that kills off nearly all crops, causing the land to fallow. Dust plagues the once prosperous farmlands.

Unlike the situation in Interstellar, our fate is within our control. The harbingers of our annihilation are not a rogue microbe or the terrorizing forces of nature. Rather, it is the misguided policy of our own state officials that guides us towards a perdition of their own making. The SGMA, with its shortsightedness and skewed priorities, is a prime illustration of what is wrong with California today: our state officials are planning for failure.2

This is a crisis that is not just affecting the farmers, but everyone in our state. We are facing a future where our children and grandchildren will not have access to the water they need to live and thrive.

Although the future we face is harrowing, this is not a new problem to California. Over a century ago, the city of Los Angeles faced a similar crisis.

Los Angeles Was Built on The Ambition of One Man

Early in her history, Los Angeles’ survival was determined by the ambition of a single man: William Mulholland.

When William Mulholland arrived in Los Angeles in 1878, her water was scarce. Families bathed once a week. First the father, then the mother, and then the children-- all using the same ration of water in an outdoor bathtub. Only the patriarch of the family was granted clean water.

Mulholland recognized the true value of water and was obsessed with securing an abundant supply for the people of Los Angeles.

After trying his hand at a few odd jobs, eventually Mulholland got a job as a ditch-digger for the LA City Water Company. There was not a lower position a man could obtain.

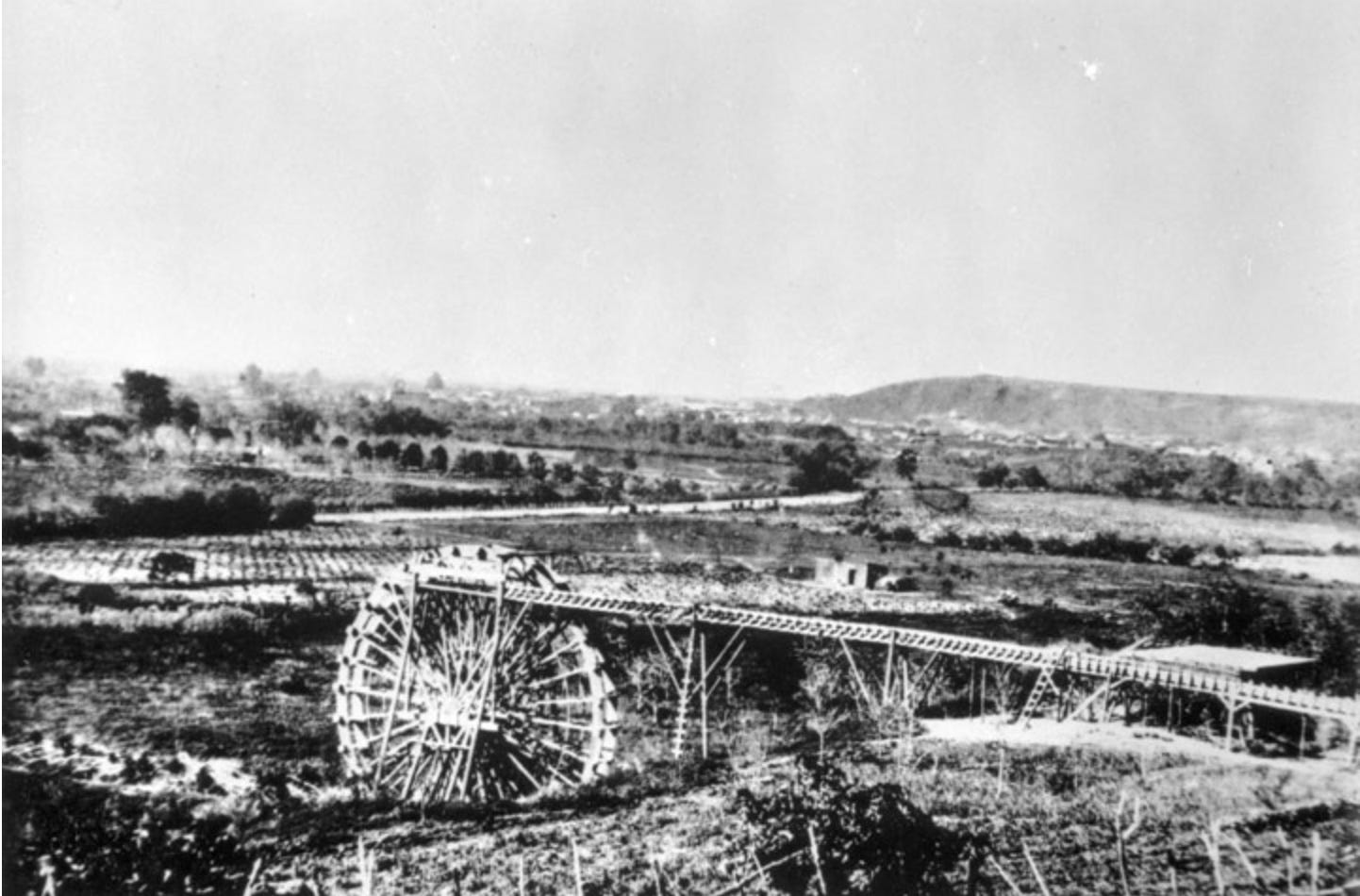

At the time, the Los Angeles water system was rudimentary, consisting of a 40 foot wheel that drew water from a reservoir and utilized gravity to direct the flow of water to civilian homes.

Mulholland was an Irish immigrant who never even finished grade school. Despite this, he was able to quickly rise through the ranks of the LA City Water Company over the next two decades. When the city decided not to renew the company’s charter, they replaced it with the municipal-owned Department of Water. Fred Eaton, the Mayor at the time, appointed Mulholland as its first head in 1898.

Los Angeles’ population grew from a humble 10,000 to an astonishing 100,000 in the span of a mere two decades, thanks to the success of the Chamber of Commerce's advertisement and the completion of a new railroad. Such exponential growth was an emblem of our nation's unwavering conviction to realize its manifest destiny.

However, such an extraordinary surge presented challenges to the city's leaders, demanding their swift adaptation to the exigencies of growth. The Rio de Los Angeles was quickly diminishing, and the rapidly growing population was faced with a grim reality: there simply wasn't enough water to meet their needs. Los Angeles faced her first water crisis.

Determined to save the city, Fred Eaton convinced Mulholland to traverse north in a horse and buggy with him in search of water. 200 miles and 2 days later, Mulholland and Eaton found their holy grail--the Owens Valley River, a source of water that would last Los Angeles into the next century.

“I think Mulholland must’ve changed. He must’ve seen himself as a sort of builder of a Roman masterwork. As someone who kept the great hydrologic engineering tradition alive…suddenly he became an empire builder.” -- Marc Reisner, author of the Cadillac Desert

The sight of the abundant water of the Owens Valley River transformed Mulholland. At once he understood his duty: to bring the lifeblood of his city back home to his people.

Mulholland and Eaton moved quickly. They bought up land from the farmers who populated Owen’s Valley3, taking advantage of the prior appropriation laws that granted them the right to unrestricted use of water accessible by land in their possession. As chief engineer of the Department of Water, Mulholland devised a plan to build an aqueduct from the valley to the city of Los Angeles.

At the time, this project was not only visionary, it was perhaps one of the most ambitious engineering feats ever undertaken. Before its conception, the Croton Aqueduct of New York City held the mantle of the largest aqueduct, spanning a mere 20% of what Mulholland's creation would eventually cover. The final creation stretched 200 miles, a length that would have reached across both Iowa and Missouri. Because it wound through California, it had to cross arid desert, unforgiving mountains, and treacherous canyons.4

The construction of this modern marvel was not without sacrifice. In the scorching heat of the Mojave desert, temperatures soared over 110 degrees fahrenheit. 100,000 men and women worked on the aqueduct, but never more than a few thousand at a time because the strenuous and dangerous work kept turnover so high. Ironically, water was scarce for those working on the massive infrastructure project. These public servants risked heatstroke and fatal dehydration daily due to their limited water supply. Mulholland himself was present everyday, working with his lieutenants to ensure the success of his mission.

With no relief from air conditioning or refrigeration, they crossed the Mojave in 5 years. Mulholland finished the aqueduct under budget and ahead of schedule. A century later, the aqueduct still serves Los Angeles to this day.

On the day the project was unveiled, Mulholland stood exhausted in front of a crowd of 30,000 people, gathered at the foot of the aqueduct. He unfurled an American flag, and turned toward the water. As the tap was opened, Mulholland delivered the shortest dedication speech in history, a succinct yet momentous proclamation: "There it is. Take it.”

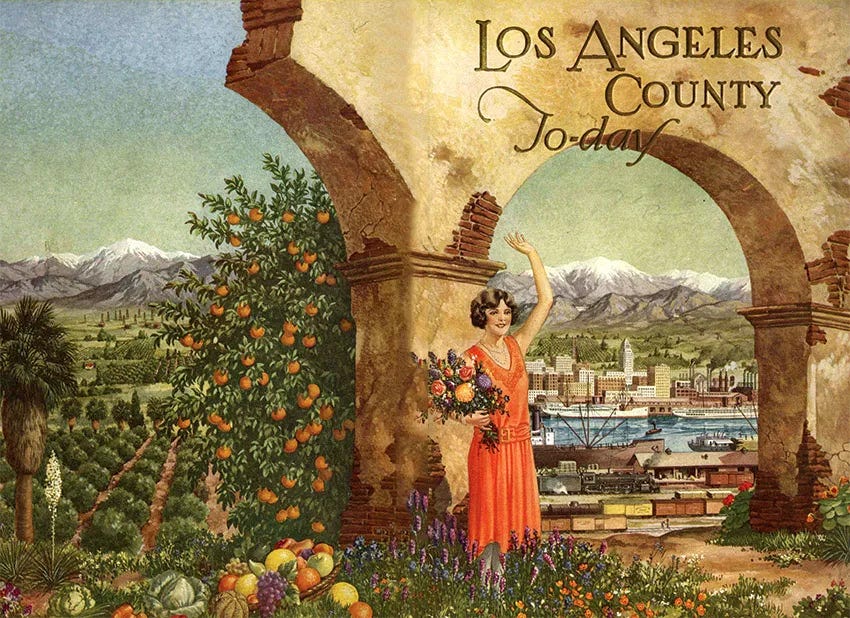

Mulholland’s leadership transformed Los Angeles from a dusty frontier city into a vibrant and flourishing metropolis. The provision of plentiful water empowered the people to master nature and transform the desert into a veritable paradise.

Innumerable palm trees, now emblematic of the city, were planted in abundance. Although these graceful trees now epitomize the beauty of Los Angeles, they are not indigenous to the region. During this epoch, Los Angeles was often likened to the Garden of Eden, an allusion to an ancient biblical prophecy which states that the desert “shall blossom like a rose."

Water spurned a golden age of building in Los Angeles that lasted through the 30s. The population blossomed from 100,000 to 1 million within the same decade the aqueduct was completed.

Not only did water rescue the city from drought, it was also the invigorating force that brought contemporary Los Angeles into being.

Our Generation Needs to Build Our Way Out of This Crisis

In modern-day California, we are confronted with a water crisis not unlike the droughts of the early 1900s in Los Angeles. The state's population has surged to over 35 million, but our water infrastructure is frozen in time. Built primarily in the mid-20th century, this antiquated system is struggling to keep pace with the expanding demand, endangering our society’s ability to thrive.

Meanwhile, as the state tightens its grip on water resources, a looming darkness descends upon California. This solution, deemed as righteous, is in fact a wolf in sheep's clothing, stripping the land of its vitality and exposing its residents to a fate worse than thirst. A plague of decay takes hold, withering the once-lush farmlands and leaving the people destitute, forcing them to abandon their homes and the American Dream. The downfall of California's imperial supremacy is but a mere symptom of the larger problem at hand - the erosion of the human spirit, all in the name of conservation.

We can fight this. A century ago, William Mulholland dedicated himself to protecting the future of Los Angeles with limited technological resources, which pale in comparison to the vast technological advancements at our disposal today.

California is a state graced with abundant blessings, where all of the tools necessary to foster progress are within arm’s reach. The reserves of brackish groundwater in the United States are 800 times greater than total consumption, but they remain essentially untapped. California's proximity to the ocean presents opportunities to tap into its limitless water resources. We possess the power to even generate rainfall through cloud seeding, a testament to the incredible power of human ingenuity.

California has two possible futures: in one vision, lush gardens and fruitful farmlands thrive in the sun-soaked terrain. The land buzzes with prosperity and industry. Majestic mountains, rolling hills, and pristine coastlines are teeming with life, beckoning travelers from around the world to bask in their natural beauty.

Or, become a barren wasteland. The once-flourishing gardens reduced to dust and ash. Farmlands lay fallow, unable to support life, and the only sound to be heard is the haunting echo of emptiness. The population dwindles as people flee the desolation, leaving behind nothing but a landscape devoid of life and vitality.

The choice is ours. Will we rise to the challenge and take bold action to secure California's future, or will we allow this great state to wither away into nothingness?

Thank you to Jane Gatsby, Dival Banerjee, Augustus Doricko, Shingai Thornton and John Forstmeier for providing feedback on this essay.

Coined by Augustus Doricko, in Planning for Failure.

It is a curious fact that Theodore Roosevelt was invested in the success of Mulholland’s aqueduct. He surrounded Owen’s River Valley with a national forest to make it off limits to further development, despite the only trees in the area being the orchards grown by Owen’s Valley farmers.

They say you could trace the path of the aqueduct from the whiskey bottles Mulholland and Eaton had thrown off the back of their horse buggy on their quest in 1904 to find a new source of water.

This is a delightful article and luv the historical foray, esp about Mulholland's life