From Hair Care to Nuclear Scare

How Hard Water led me to Discover Nuclear Fear's Role in Transforming America

Two years ago, I set out to understand water scarcity in California.

The way it all started was rather embarrassing: I was not drawn in by a studied contemplation of climate models or policy briefs — Los Angeles’ hard water was wreaking havoc on my hair.

That seemingly trivial concern led me down a rabbit hole to a startling discovery: California is planning to deliberately abandon nearly 1 million acres of the world's most productive farmland.

One might expect insights into the vulnerabilities of the country’s food supply to emerge from more dignified inquiries. Yet, there I was, tracing the path from damaged follicles to farmland fallowing.

I’m a chronically curious person—to a fault. My curiosity claws at me until I’m subsumed. This time was no different. Suddenly, I was obsessed with why we stopped building infrastructure.

So I did what any normal person would do: I started reading. A lot. Legal documents, policy briefs, judicial cases. Six months passed, and I was still waking up every morning with the same compulsion: to know more. (I’ve printed over 1,000 pages of documents—yes, I still have them all, sitting in a storage locker somewhere in LA like evidence from some bureaucratic crime scene.)

A History of Abundance, A Future of Scarcity

California’s prosperity has always been shaped by its unique geography and bold interventions. In the early 20th century, the state embraced a modernist ethos, one that prioritized human ingenuity over natural constraints. Water management policies focused on capturing and storing rain during wet years to endure inevitable droughts. This ethos was so strong that, in 1928, Californians amended their constitution to enshrine the reasonable and beneficial use doctrine, effectively outlawing inefficient water use.

By the 1960s, California’s ambition had created a formidable network of 1,400 dams and 1,300 reservoirs, successfully transforming the state’s volatile rainfall patterns into a reliable water supply. Yet, by 1969, priorities underwent a dramatic transformation. Water, once celebrated when harnessed for human benefit, was now deemed wasted if diverted from natural ecosystems, marking a profound ideological shift.

Today’s water allocation tells a story of this dramatic shift: California dedicates 50% of its water to environmental purposes, 40% to agriculture, and a mere 10% to urban and industrial use. Despite a 70% population growth since 1979, the state has built only one major water supply project in the last four decades.

This isn't a story of natural drought—it's a chronicle of deliberate policy choices. The restriction of infrastructure development and prioritization of environmental flows over human and agricultural needs had created a crisis of scarcity where abundance once flourished.

The Atomic Age’s Shadow - The Legacy of Apocalyptic Thinking

What cultural forces had shaped an environmental movement so opposed to human intervention in nature? Why had we shifted from seeing environmental modification as progress to viewing it as inherently destructive?

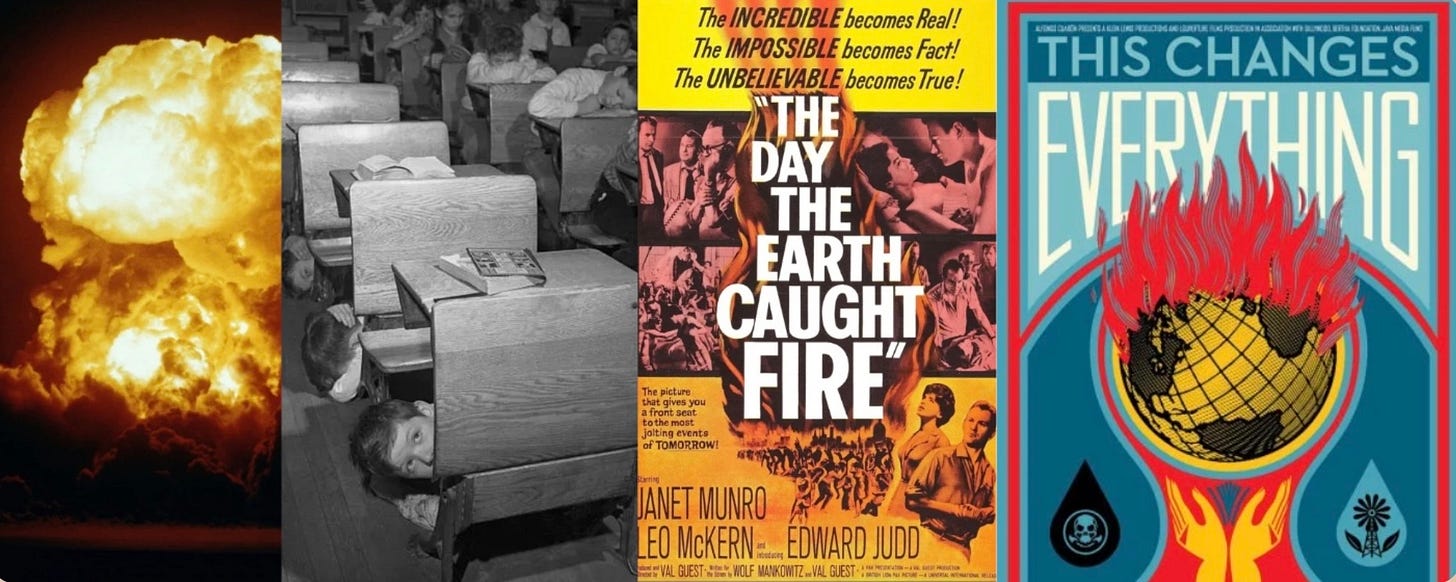

These questions led me to examine the philosophical underpinnings of modern environmentalism. Looking at the environmental movement's early leaders - Rachel Carson, Paul Ehrlich, Stewart Brand, Stephanie Mills - I noticed something they all shared besides their ecological concerns: they were all children of the atomic age. Their formative years were spent beneath school desks during nuclear drills, watching mushroom clouds bloom on television screens. They lived in a world where a human-caused apocalypse wasn't just possible - it felt inevitable.

The more I dug, the more I saw how the psychic wounds of the atomic age had infected our relationship with technology and progress. The imagery of environmental catastrophe maps perfectly onto nuclear devastation. The fear of human hubris leading to apocalypse. Even the visual language is the same - just replace the world on fire from nuclear apocalypse to it burning from climate change.

I'm still tracing these connections through philosophy and cultural history, from René Girard's mimetic theory to Camille Paglia's analysis of the archetypal relationship between man and nature. But one thing is becoming clear: the way we think about progress, nature, and human creativity today is haunted by the ghosts of atomic fear.

And yes, I eventually fixed my hair problems. But by then I was chasing bigger questions: How did we become so afraid of our own creative powers? And what's the real price we're paying for that fear?

This is ongoing research into California's water scarcity and its connection to nuclear-era anxieties. To follow these findings as they develop, consider subscribing. If you believe this work matters—as I do—in preventing domestic food insecurity by understanding the cultural forces behind our failed policies, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.